Abstract

This monograph discusses the threats and opportunities posed by the ageing population in Europe. It identifies the actions that need to be taken to make these demographic changes an opportunity for economic growth and for increased quality of life for the citizens.

THE DEMOGRAPHIC IN EUROPE IS CHANGING

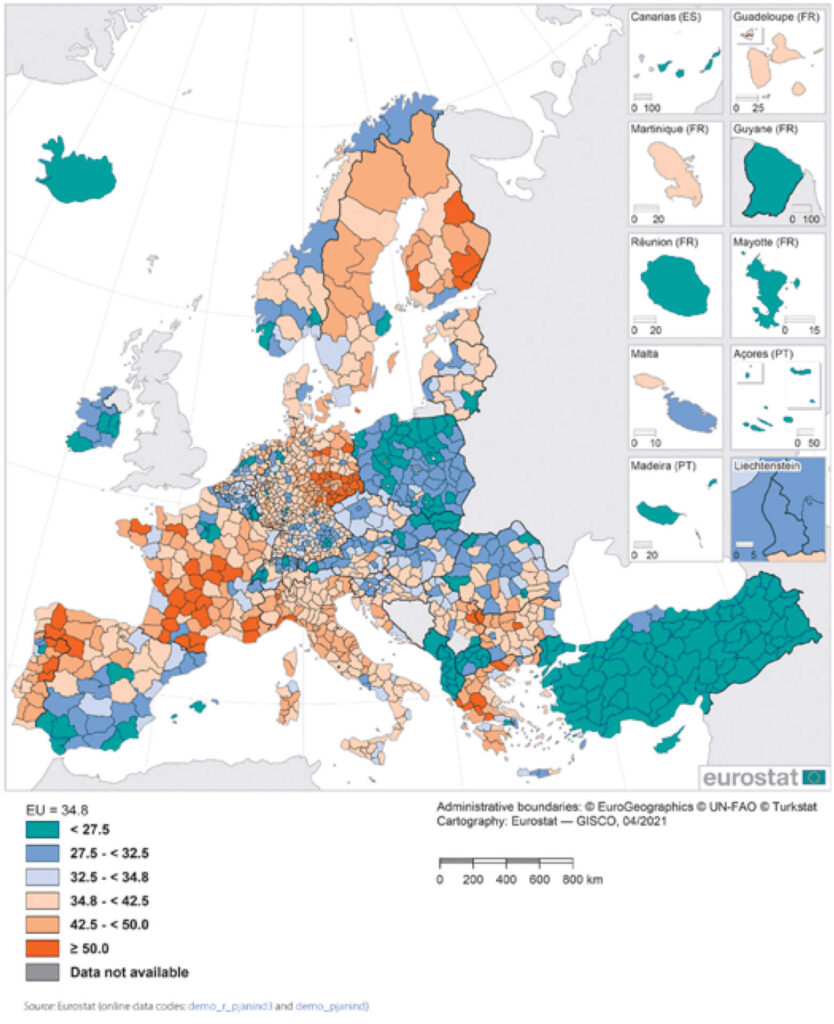

The ongoing demographic shift towards an older population in medium and higher income countries poses both challenges and opportunities for governments, organisa- tions and individuals. The European Union is ageing rapidly and according to Eurostat the proportion of people aged 80 or over is expected to grow from 5.4 % in 2016 to 11.4% of the population in 2050. The median age of the EU population is increasing continuously and stood at 43.9 years in 2020. A visualisation of the ageing of the European population can be made by calculating the number of elderly people (aged 65 years or more) divided by the number of working-age people (defined as those aged 20-64 years). In 2020 this ratio was 0.348 and by 2050 it is estimated to be 0.567. This means that in 2050 there will be fewer than two working-age adults for each person over 65.2 These dependency ratios for European regions during 2020 are shown in Figure 1.

THE CHALLENGES OF AN AGEING POPULATION

The ageing population as illustrated in the increasing dependency ratio leads to the following challenges:

A reduction in the available labour force

According to Marois et al3 the available labour force in the EU will reduce from around 246 million in 2020 to 230 million in 2050. Over the same period the European GDP will increase from $20.9 trillion4 to a forecasted $31.3 trillion.a, 5 These numbers indicate (everything else being equal) an average annual increase in labour productivity of 1.6% compared to historical numbers of an average less than 1%.6

Some mitigating actions to address the labour force decline and the productivity gap are:

- Putting in place policies (from government) and practices (from employers) that enable individuals to stay in the workforce beyond the present retirement age. To stabilise the labour force the average European working life needs to increase by about 7 years7.

- Adopting productivity improving technologies to both substitute for labour and complement labour. This will necessitate competence and capability building as well as process and work practice changes (and sometimes changes in the relevant business model).

- Increasing the share of women in the workforce to a level comparable to men of the same age and the same education

- Increased absorption/integration of immigrants into the workforce achieving a participation level similar to those in the domestic workforce with the same age and educational Workforce immigration is an important strategy but accepting immigration with zero or very low educational level becomes very expensive and also puts the labour productivity objective at risk and hence the GDP growth.

- Labour force participation is strongly correlated with educational attainment8 Implementing policies that reduce and preferably remove the disadvantage in educational achievement for children of low-educated mothers and those with an immigrant background becomes

The first two mitigation points relates directly to the ageing part of society whereas the remaining three points relate only indirectly to the ageing part of society (and will hence not be discussed).

The benefit of a multigenerational workforce is clear. A firm that has a 10% higher than average share of workers aged 50 and over is 1.1% more productive and has 4% lower employee turnover.9 CEO’s and other managers are between 2 and 2.5 years older in the 20% most productive firms as compared to the 20% least productive.10, 11 These benefits accrue from older workers being more productive on average than other workers as well as productivity-enhancing complementarities between employees of different age e.g. through teams where younger and older employees work together leading to spillover of knowledge and experience.12 Building a multigenerational workforce also yields a stronger pipeline of talent, increases resilience and improves workforce continuity, stability and the retention of know-how.13 The benefits can be summarised under the headings:14 Increased productivity; Stronger talent pipeline; Greater diversity of skills & outlook; Better retention of experience & know-how; Increased resilience; and Better access to multi-skilled teams. To access these benefits employers must have a life-cycle oriented approach to workforce strategy; unbiased recruitment; managerial training; internal mobility; identification and fulfilment of training needs; mid-life career reviews; job-rotation and shadowing; action learning; health promotion and promotion of healthy work; career support; job design and job adaptation; multi-stranded flexible working policy.

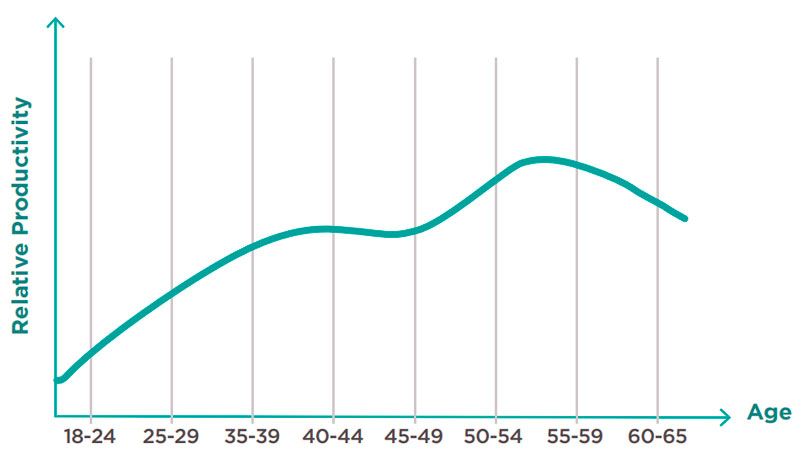

It is also worth noting that productivity changes with age and although it declines slightly after age 55 it is still remains substantially higher than the productivity of those aged under 40 as shown in Figure 2.

Increasing costs for Health and Care services

Evidence from the Medical Expenditure Survey (MEPS) in the United States shows that 42% of those that incur high medical costs are older than 65,16 and the most common conditions are hypertension, osteoarthritis alongside a number of other chronic conditions. Although ageing is not a negligible driver of health care costs, there are good reasons to argue that the effect of ageing on health expenditure is overestimated since a significant share of expenditures take place around the time of death – at whatever age death does occur.17 When time to death is accounted for, the effect of ageing on health costs disappears.18 Felder et al.19 have shown that the effect of time to death decreases with age and Seshamani & Gray20 have shown that hospital expenditure increases well over 15 years before death, and declines once an individual turns 80. Costa-Font & Vilaplana-Prieto21 in an excellent empirical study with high validity and European relevan- ce finds that:

- Proximity to death increases hospitalisations, length of hospital stays, long-term care use (home and nursing home care), and outpatient care

- The effect size of proximity to death exceeds that of an extra year of However, their estimates are heterogenous across different types of health care. Morespecifically, they find that ageing does not increase the utilisation of outpatient care. Furthermore, the effect of ageing is attenuated when comorbidityb controls are included in explaining both the extensive and intensive margin of hospitalisa- tions and medicine consumptionc.

- They estimate that an additional year of life decreases the length of stay in nur- sing homes by 13%. The largest impact of age corresponds to the frequency ofhome-based assistance for personal care because each additional year increases the probability of receiving one additional hour of assistance by 13.6%.

The study concludes with the statement that: These results taken together indicate that estimates of the effect of ageing on hospital care utilisation are attenuated, or become insignificant, when alternative explanations of an ageing effect such as endogenous time to death and the influence of comorbidities, as well as omitted variable bias, are accounted for.

The conclusions are that ageing is in itself not a key contributor to the increased health care costs in Europe which fits with the findings of Gill & Taylor22 that the proportion of the increase in annual spending in the British National Health Service that is due to population ageing is only 1.5%.

From all the studies reviewed it seem that the key drivers of increased health care costs in most European countries are due to increasing costs of technology, increasing costs of pharmaceuticals and increasing labour costs. Two further potential contributors are low productivity improvementd and increasing administrative costse.

Increasing pension costs

With increasing age come pressures on national pension systems. In response to this pressure several countries have raised the lower age limit for early pension or for the default state pension age as well as limiting the economic conditions for early pension and/or improved the conditions for late exit.23 The raising of the lower age limit and the encouragement to stay in work will, if successful, increase the numbers of older workers. The success of this policy is also dependent on the attitudes and practices of employers, and it is questionable how well employers are prepared for this ageing of the labour force.24 In an interesting study of Norwegian workers above the age of 67, Salomon & Solem25 found that they were characterised by valuing the intrinsic aspects of work highly, having a history of working many hours, having a strong engagement in work, having an inner drive for work, and not wanting to disassociate themselves from work. There was also a very high share of self-employed among those aged over 67 that worked.

The restrictive effect of mandatory retirement is to some extent supported by the finding of Solem et al.26 that some managers re-engage mandatorily retired employees as self-employed to do the same tasks as they did before.

Pension systems differ in how much they confirm, exacerbate, or reduce social inequalities, since modern public old-age pension is a combination of general basic security and individual income-related pensions. 27 Therefore, simply extending working life also represents a risk of increasing inequalities between pensioners.28

It is clear that the old-age pension costs will increase substantially given the ageing trends unless policy changes are made and unless employers change their attitudes towards older workers. Dang et al.29 made the following forecast (Table 1).

Zwijnenburg & Goebel, 201731 found that an ageing population will lead to increases in pension and health care costs, which will outweigh decreases in costs related to child and family benefits and education. They also found that the impact on pension schemes will depend on the institutional setup of the schemes. Depending on the scheme, these changes may affect the sustainability of pension funds and government finances, and household retirement resources. This explains the legislative drive towards changing the pension systems in most countries.

THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE AGEING POPULATION

The societal contributions of older adults are frequently not mentioned in the public narrative. Using the UK as an example, it is estimated that over 65s make a net contribution to the UK economy of £40 billion, after deduction of the costs of pensions, welfare and healthcare costs, through tax payments, spending power, donations to charities, volunteering, as well as financial and other types of support for relatives.32

A survey in Britain in 2011 revealed that people over 65 are a substantial proportion of volunteers in voluntary organisations, which are important providers of various forms of welfare in Britain, working closely with state welfare agencies. About 30% of over 60s volunteer regularly.33 In addition, many older people provide informal voluntary services by assisting relatives, friends and neighbours (many of whom are also retired) as well as older women caring for frail husbands and for disabled adult children, saving the state welfare services a considerable sum.34 The value of formal volunteering by older people in the UK is estimated at £10 billion annually saved to the budget of public social services and the value of informal social care at £34 billion. 35 Moreover, the value of childcare service provided by older people is estimated at £3.9 billion annually.36

A further contribution is made by “the bank of mum and dad” which also includes grandparents. For example, 31% of British grandparents save to help grandchildren buy a home.f 16% in their 60s and one-third in their 70s give financial support to grandchildren, including paying school and university fees, and, increasingly to their children.37 It is only when grandparents reach age 75 or older that they are more likely to receive more than they give in financial and practical help to younger people.38

THE OPPORTUNITIES OF AN AGEING POPULATION

SAPEA39 states that at the individual level, the ageing process is extremely heterogeneous, as huge social and cultural variations have a significant impact on the quality of ageing. However, ageing is usually preferred over early death, as it gives people a second, third and even fourth chance at life and provides multiple opportunities for personal fulfilment. This should not be overlooked but rather celebrated, as ageing represents a continuing chance to redefine oneself during life.

On the societal level rapid changing societal structures, such as smaller and more frag- mented family units, the co-development of age discrimination and health inequities, and the emergence of new geriatric syndromes and longer periods of disability, greatly impact labour force, pensions, and social and health care costs – as discussed above. However,as SAPEA states, ageing overall allows for increased productivity, greater work expertise and intergenerational exchanges of material and non-material goods (e.g. education and experience), thus forming bonds between young and old generations. In addition, the increasing population of older people provides a growing market in its own right.

A growing market

The increasing share of older peopleg in the economy alongside an ageing population means that there is a growing market for products and services for older people – the estimated size of this market in the US during 2020 is $8.25 trillion and $14 trillion globally with an annual average growth rate of 4.1%. This market is driven by the combined spending of public and private sector on the specific needs of older adults where the private sector spending will be underpinned by the relatively high net wealth and spending power of the older consumer. The importance of this market is illustrated by the fact that it is expected to account for over 50% of US and Japanese GDP by 2030.

The justification of this number comes from the increased dependency ratio (discussed above) and the fact that those aged 55 and over account for 55% of all household expenditures and 75% of all wealth in the EU.

It is important to insert here the obvious caveat that the ageing market is as diverse as it is possible to get and hence from a service or product provider’s perspective it is essential to define the target market precisely.

The key opportunity in this market emerges when technologies meet market needs. The needs and the technologies are illustrated in Figure 3.

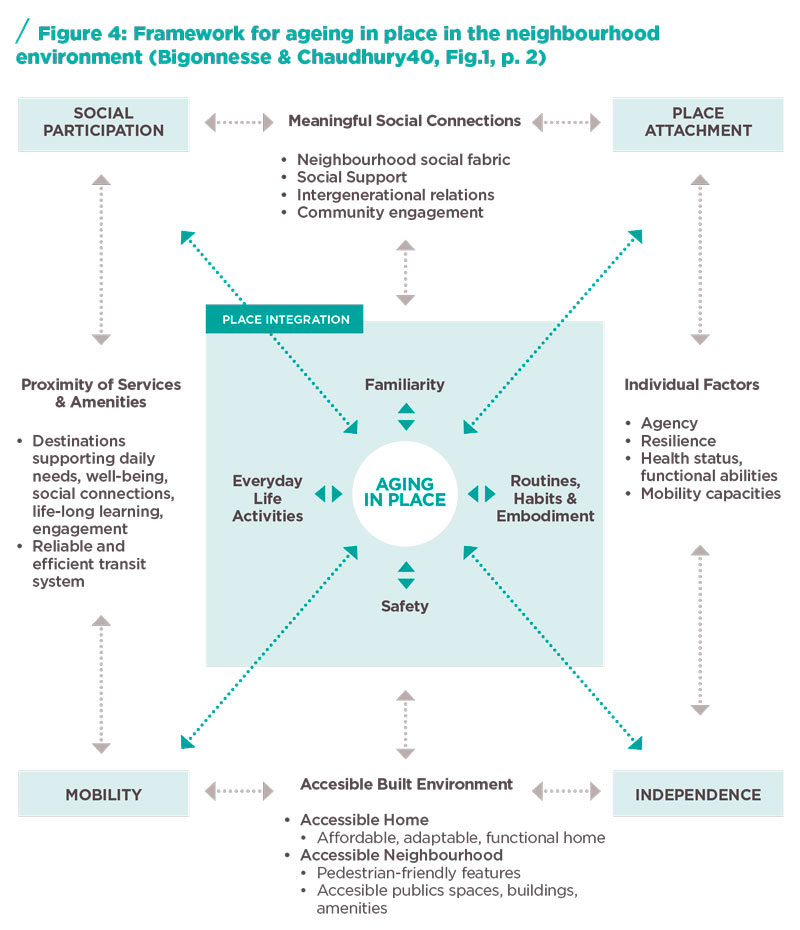

Aspects of what is shown in Figure 2 are closely related to the framework for ageing in place in the neighbourhood environment as developed by Bigonnesse & Chaud- hury41 and shown in Figure 4. Given the emphasis from both policymakers and indi- viduals on increasing the ageing in placeh opportunities, this further increase these market opportunities.

Integrating the elderly into the design process

The spending on health-related R&D in many countries is very high (and in the US, it is second only to the spending on defence R&D). The success rate of this spending is generally low due to a large gap between the R&D objectives and contexts and the real-world implementation context. These failures are due to many factors including:

- An overly simplistic view that pilots and prototypes will naturally scale-up to mainstream 42

- Researchers who work (their whole life) within academic institutions frequently lack the insight and skills needed to create viable commercial products or services, whilst the ‘publish or perish’ culture in academia frequently counteracts any desire to commercialise the research output.

These reasons for failure are likely to be the same for products and services focussed on the elderly and specifically so for technology-based products and services (known as gerontechnology products).

- Start-ups are important in the gerontechnology domains but the products or servi- ces as well as the companies frequently fail. The latter due to weak management in combination with poor access to capital and the former due to experience distance between those that develop the offering and those that use it which is why real-life verification is more important in the gerontechnology domain than in many other domains. Without the consideration of users, entrepreneurs who are often significantly younger run a risk of misunderstanding or misinterpreting needs and create mismat- ches between gerontechnology solutions and consumer demands. Fritsch et al.43 also identified that much attention is put on care situations where the image of the elderly is that of sick or disabled persons not mastering contemporary information technology in spite of that group being only a fraction of the group called the elderly.

- Any solution or service created should thus be co-designed with users and their behaviour Therefore, Living Labs are critical in both the co-design phase and the verification phase.

A Living Lab can be defined as: “an embodied research methodology for sensing, prototyping, validating and refining complex solutions in multiple and evolving real life contexts. In essence it applies a design methodological approach within a semi-open innovation frameworki to enhance the fast-prototyping co-creation thinking when it comes to products, services and solutions that are either systemic in nature or part of a greater systemic/holistic setting”. 44

Empirical studies have shown the need for assistance with verification of appropriate- ness of new products and services developed for the gerontechnology market45 where Lepik & Krigul46 identifies that over 50% of companies developing these types of products and services are looking for assistance with validation.

Given the user-provider information asymmetry and the developer-user experience distance in the gerontechnology sector, access to and functioning of a gerontechnology focused Living Lab is critical for the development of successful gerontechnology offerings.

- The macro or organisational level, where the Living Lab is a set of actors and stake- holders organised to enable and foster innovation, typically in a certain domain or area, often also with a territorial link or focus. These organisations tend to be Pu- blic-Private-People partnerships.48

- The meso or project level, where Living Lab activities take place following a mostly organisation-specific methodology to foster

- The micro or user activity level, where the various assets and capabilities of the Living Lab organisation manifest themselves as separate activities where users and/or stakeholders are involved.

What distinguishes the Living Lab approach from other, more traditional supplier-customer partnerships, or previously seen cross-disciplinary approaches is the ability to interact with users.

The Living Lab methodology, with the common elements and identified innovation pro- cess, can be situated at the meso level, where the projects are structured based on it. The following principles are core to Living Lab methodologies: active user involvement, real-life experimentation, multi-stakeholder and multi-method approaches. Besides these main principles, another common aspect within Living Lab methodologies relates to the different stages that are followed in an innovation process. From the perspective of the ‘innovator’, it is possible to distinguish between the ‘current state’ and the ‘future state’,49 where the existing, ‘current state of being’, the ‘as-is’ or ‘status quo’ is opposing ‘possible future states’.50 This resonates with design thinking, which proposes an iterative approach, based on:

- A large part of this phase is the collection of data to be analysed and this is frequently done through observation, which explains the role of LivingLabs in the design-based innovation process. The core issue of analysis is to assemble, from a virtual infinity of information, whatever is relevant. This information is then detailed and structured, so the implications become sharp and clear. Probably the prime failure of most complex design projects is a tendency to make analysis too casual.

- In genesis, the messages of analysis are deliberately improved. The essential activity in this phase is generating new information through the application of intelligence (i.e., the search for insight through simultaneous new discoveries at many levels).

- The visualisation of the outcomes of genesis in the real context (i.e., prototyping). Synthesis doesn’t materially improve a product as genesis does but if skilfully done, it can contribute enormously to the product’s value.

These iterative phases facilitate experimental learning, and alternate between divergent thinking and convergent thinking.51 The objectives of design are to achieve behavioural change in the user which is desirable from the users’ point of view (i.e., they are better off in their own opinion after the change), to benefit the suppliers of the product or service, and to positively impact other stakeholders.52 Action research is then used as a method to build these methodologies out of concrete cases and projects, carried out within the Living Lab.53

To anchor the individual user involvement activities (micro level) with a methodological framework that follows this design reasoning, Schuurman et al.54 proposed that Living Lab projects resemble a quasi-experimental approach. This includes a pre-measurement, an intervention and a post-measurement, where the intervention is equalled to the real-life experiment. Following the above reasoning, we can distinguish three main building blocks within Living Lab projects after the innovation development phases:55

- Exploration: getting to know the ‘current state’ and designing possible ‘future states’. The main goal of this stage is to understand the ‘current state’.

- Experimentation: real-life testing of one or more proposed ‘future states’.

- Evaluation: assessing the impact of the experiment with regards to the ‘current state’ in order to iterate the ‘future state’.

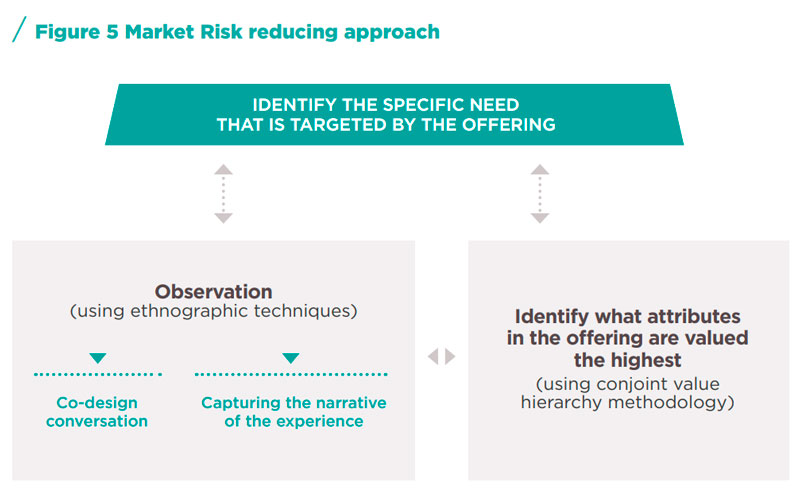

Living Labs provide an opportunity not only to enhance the usability of a product or service developed for the ageing market (a market characterised by high levels of in- formation asymmetry and hence an inefficient market) but also to identify the specific target segment. The methodology for this is outlined in Figure 5.

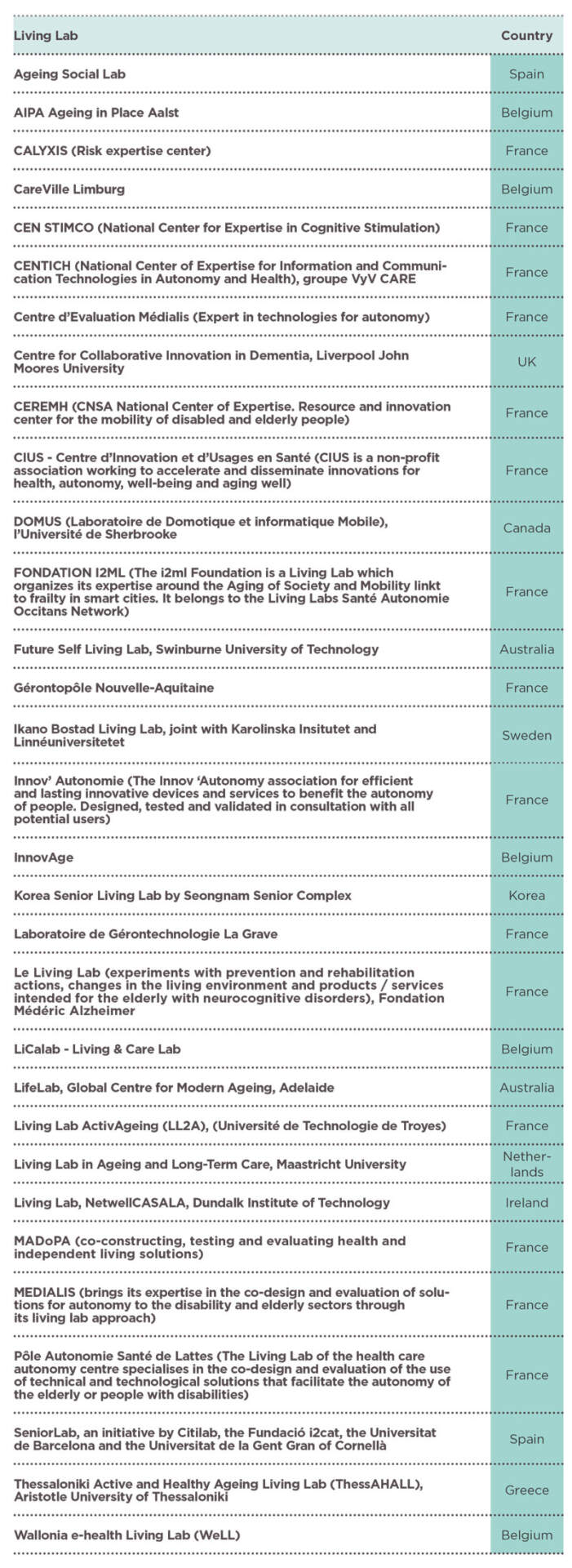

There are Living Labs that focus totally or in part on the ageing market. Some examples are:

The Macro Perspective

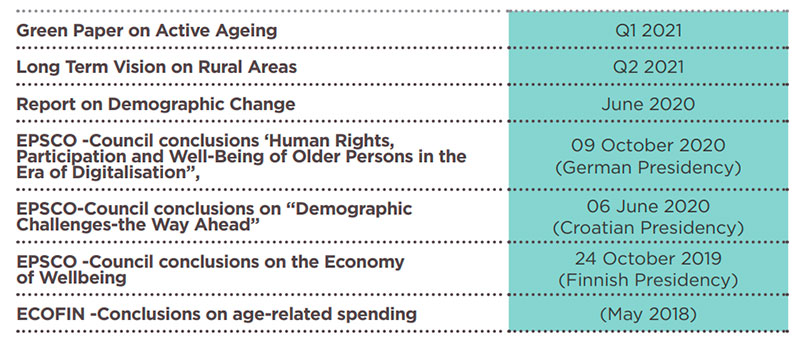

The growth of this market has generated both public and private actions. The European Commission has launched multiple smart ageingj platforms focusing on technology, regulatory issues, and potential future markets. Some of these are: The Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programme, the More Years Better Lives Joint Programme, and the European Innovation Partnership for Active and Healthy Ageing. The EC Policy Framework “Smart Ageing” has so far generated:56

The EU funded SHAPE (Smart Healthy Age-Friendly Environments) project has in its D4 Report57 mapped the national policies, strategies and funding with relevance to Smart Healthy Age-Friendly Environments.

On the global level there is the Aging 2.0’s Grand Challenges initiative to drive collaboration around the biggest challenges and opportunities in ageing. These are stated as being:58 Engagement & Purpose; Financial Wellness; Mobility & Movement; Daily Living & Lifestyle; Caregiving; Care Coordination; Brain Health; End of Life. In addition, some countries have established clusters and other state promoted activities. Examples are:

- The UK Ageing society grand challenge with the mission to:59 ensure that people can enjoy at least 5 extra healthy, independent years of life by 2035, while narrowingthe gap between the experience of the richest and poorest. Success in this mission will help people remain independent for longer, continue to participate through work and within their communities, and stay connected to others to counter the epidemic of loneliness.

- Ireland identified that there is potential to build Ireland as a preferred location for international companies seeking to research, develop and trial new approaches to addressing the challenges and opportunities for an ageing population, and optimise the commercial exploitation of scientific breakthroughs emanating from research centres and businesses in Ireland. 60 This potential built on the existing capabilities in Medical Devices; ICT mobile communications; ICT sensor technologies; Internet technologies; ICT/data analytics/Software; Business services; Healthcare services; and Functional foods. Ireland also has ISAX (Ireland Smart Ageing Exchange) which is a network of businesses, academic institutions and government agencies interested in solutions for the global ageing economy. They provide support including training, workspace and an accelerator for entrepreneurs over the age of 50 as well as any entrepreneurs developing products for older people.

- Silver Valley outside Paris (in Ivry-Sur Seine) has attracted more than 300 members, 46% of which are start-ups and 54% of which are large international In 2018 Silver Valley created the Open Lab, a unique sociological mechanism in France integrating about 10,000 people aged 55 to 92, who share their ageing experiences throughout the year and thereby enable the joint exploration of the associated innovation pockets.61 The offering in the French Silver economy domain is made up of services only (31%), integrated products and services (21%), manufactured products only (18%), digital goods onlyk (10%), integrated manufactured products and digital goods (8%), integrated services and digital goods (6%), and investments (6%).62

- Scotland’s Healthy Ageing Innovation Cluster, which is facilitated by the Digital Health & Care Innovation Centre, on behalf of key partners including the Scottish Government’s Technology Enabled Care Team, The Digital Office for Local Government, Scottish Enterprise, Highlands & Islands Enterprise, Enterprise Europe Network and the European Connected Health Alliance.

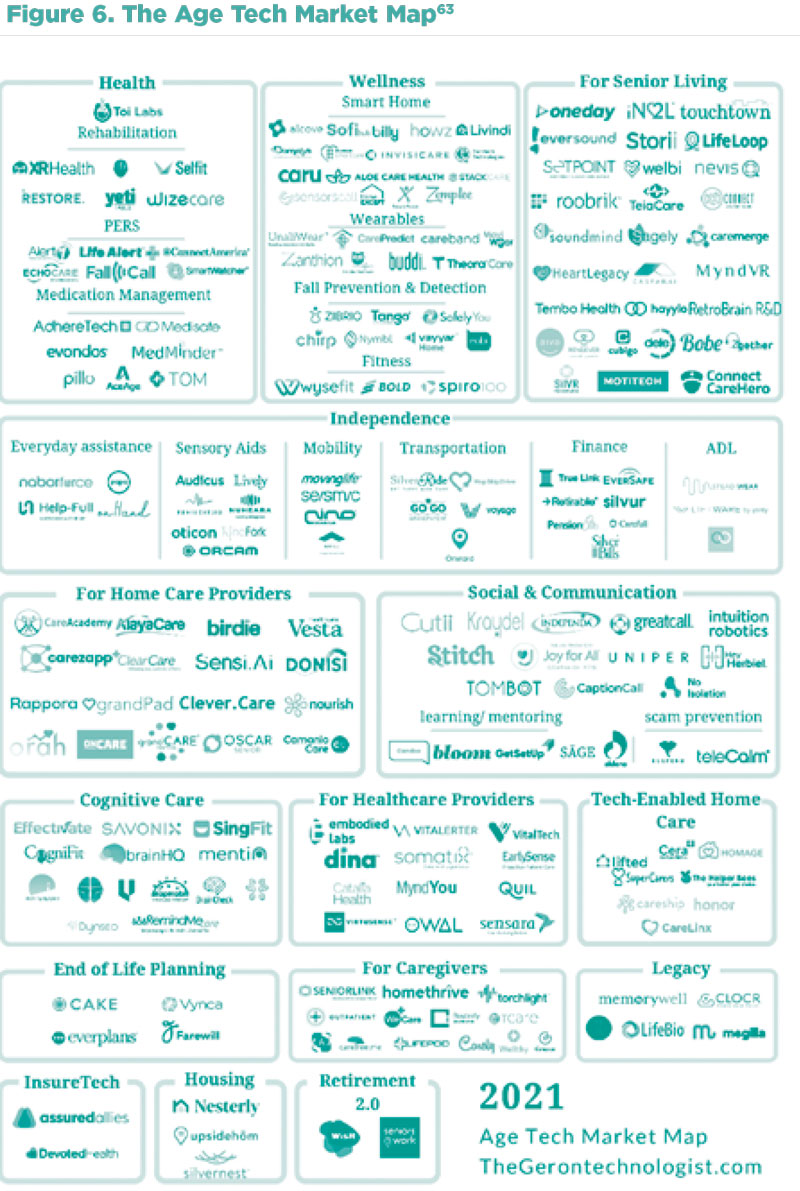

The business interest in the segment can be illustrated by mapping companies in the different emerging product-service offering segment resulting from the matching of opportunities and technologies illustrated in Figure 3, as done by TheGerontechnologist.com and shown in Figure 6.

A good discussion of the attributes of the silver economy can be found in Iparraguirre.64

OLDER PEOPLE IN THE WORKFORCE

As people live healthier and longer lives, they may (choose or be able to) work later in life, thereby increasing economic activity at older ages. To maximise the opportunities of the ageing population a number of actions must be taken by governments, employers, individuals and other stakeholders. These include (partly extracted from SAPEA)65:

- Aim to decrease the prevalence of ageisml in society. Ageism impacts all aspects of our lives and is manifested at the cultural and institutional level, at the family andrelational level, and at the individual level.66 At the cultural and institutional level, ageism determines what policies and legislation are developed, for example defining premature death as occurring prior to the age of 70,67 and imposing a mandatory retirement age,68 which forces older people to become dependent on their life savings and old age pension. Ageism in the health and care system takes many forms but those most important to address relate to the tendency to offer medical inteventions for social conditions,69 shortage of health and social care workers willingto work with older adults,70 the high prevalence of negative attitudes towards older adults reported by health care professionals,71 or a tendency of paternalistic treat- ment which disregards older people’s autonomy.72

- Aim to remove implicit ageism in the built environment.73 An interesting approach can be found in Aliramaei (2021).74

- Aim to remove ageism in the workforce manifested through the mandatory retirement age which is enacted in many European countries despite laws that prohibitworkforce discrimination based on age. Also educate employers of the positive effects of having a multigenerational workforce (increased productivity etc. as discussed above) and how to structure the organisation and the work processes to maximise these benefits.

- Aim to reduce the extent to which individuals internalise negative perceptions towards their own These negative attitudes risk leading to prematuredeath,75 physical impairments,76 fall,77 deteriorating cognitive functions,78 recovering more slowly from disability,79 and higher levels of loneliness.80

The reality of how employers address this issue varies substantially between coun- tries in Europe as well as between employers within countries. Cebulla & Wilkinson81 found in their study a marked between-country difference, with UK case studies highli- ghting a strong emphasis on age-neutral practices shaped by legislation; age-confident practices in Germany resulting from collaborative arrangement between employers and trades unions (with legislation permissive towards age discrimination); business

in Spain remaining relatively inactive, despite evidence of people expecting to work longer in life. A detailed summary of country policies for 34 countries relating to extending the working life can be found in Ní Léime et al.82

CONCLUSION

It is clear from the above that the ageing population in Europe can be an opportunity for both economic growth and increased quality of life but that this will not happen unless several actions are taken by governments (regional, national, and supra national), employers and individuals. The key actions are:

- A recognition that the older individuals in society are as diverse as the rest of the individuals in society.

- The removal of ageism in society at all levels and in all The key initial action should be to remove the compulsory retirement age and make it easy and tax beneficial to mix part-time work with drawing down part of the pension allowance and thereby incentivising individuals to stay in the workforce beyond retirement age. It however needs to be noted, that some individuals have had work in which they have been physically or mentally worn out and therefore need to retire earlier than the normal retirement age and these individuals also need to be catered for if they are unable to do a different job in old age.

- Employers need to develop skills in how to manage a multi-generational workforce and how to combine individuals in such a workforce with appropriate productivity improving technology embodied This will improve intergenerational skill trans- fer, reduce employee turnover, and increase firm productivity.

- Ensure that regulations are not implemented that reduces incentives for the older population to contribute to society in the many forms discussed above but rather that these forms of contribution should be

- Increase awareness of the opportunity of a growing market that the ageing population This awareness should focus on both opportunities to serve existing needs in new ways and in serving new needs using new technologies as both needs and technologies emerge and mature.

- Increase awareness of how to reduce market risks for new offering to the ageing market, by involving users in the product or service development process to com- pensate for the information asymmetry that otherwise may exist between developers and users. One of the best tools for reducing the market risk and maximising the market opportunity is the use of specialised Living Labs during the development and verification phases (see Figure 5).

- On the regional and national level investigate if it is possible to create an environment for developing clusters serving one or more of the market domains if the capabilities needed already exist in other businesses or clusters in the geographical area.

If these actions are taken, then the ageing population in Europe is a great opportunity which is synergistic with the opportunities offered by digitalisation and reduction of society’s environmental footprint.

Written by Göran Roos

Member of the board of Medfield Diagnostics AB, the Global Centre for Modern Ageing, and the advisory Board of Staccato Technologies AB. He is part-time full professor (Professor II) at Kristiania University College; Visiting Professor in Business Performance and Intangible Asset Management, Centre for Business Performance, Cranfield School of Management, Cranfield University. Göran is a CSIRO Affiliate as well as a fellow of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (ATSE) and of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA).

(a) The European GDP has fluctuated up and down since 2008 and before that it was in continuous growth

(b) Comorbidity describes the effect of all other conditions an individual patient might have other than the primary condition of interest and can be physiological or psychological.

(c) They find that each additional year of life has a positive effect on the length of hospital stay (+2.3%) and on the number of medications consumed (+3.9%). This effect is six and ten times lower respectively, than the effect of an additional comorbidity.

(d) Although measuring productivity in health care is challenging and different methods provide somewhat diffe- rent answers. A good discussion can be found in Sheiner, L., & Malinovskaya, A. (2016). Measuring productivity in healthcare: an analysis of the literature. Hutchins center on fiscal and monetary policy at Brookings.

(e) As an example, the administrative costs in Swedish health care increased by 21.8% during the period 2014-2017. This was the third highest increase after Information, education and advice relating to preventive health care (24.1%) and Curing and rehabilitating home care (22.8%). Data sourced from Tabell 1. Hälso- och sjukvårdsut- gifter 2014–2017 on page 45 in Socialstyrelsen. (2020). Tillståndet och utvecklingen inom hälso- och sjukvård samt tandvård. Lägesrapport 2020. Socialstyrelsen.

(f) According to the Financial Times (24th March 2021) in 2020, gifts from parents, grandparents, friends and relatives were behind more than half of house purchases among the under-35s (referencing a study by Legal & General) and this pattern of lending is expected to continue. The amount lent average GBP 20,000 and total, depending on the year between GBP 3.5bn and GBP 6.3 bn in the UK (The Guardian, 1st September 2020).

(g) In most of the economic forecast these are defined as people over 55 years of age.

(h) Ageing in place is defined as the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level

(i) Semi-open innovation framework means that it builds on the principle of crowd sourcing but the crowed is defined and delimited by the originator of the problem.

(j) Mainly composed of websites, social media, or digital tools dedicated to follow-up the health care pathway of elderly people.

(k) Defined by the World Health Organisation as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination towards people because of their age.

(1) Eurostat. (2021). Eurostat regional yearbook. 2021 edition. European Union.

(2) Eurostat. (2021). Eurostat regional yearbook. 2021 edition. European Union.

(3) Marois, G., Sabourin, P., & Bélanger, A. (2019). How reducing differentials in education and labor force participa- tion could lessen workforce decline in the EU-28. Demographic Research, 41, 125-158.

(4) https://data.oecd.org/gdp/real-gdp-long-term-forecast.htm

(5) . https://data.oecd.org/gdp/real-gdp-long-term-forecast.htm

(6) . Van Ark, B., de Vries, K., & Jäger, K. (2018). Is Europe’s Productivity Glass Half Full or Half Empty?. Interecono- mics, 53(2), 53-58.

(7) . https://stat.link/zyj910

(8) Kennedy, S., Stoney, N., & Vance, L. (2009). Labour force participation and the influence of educational attain- ment. Economic Round-up, (3), 19-36.

(9) OECD. (2020). Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer. OECD Publishing

(10) Feyrer, J. (2007). Demographics and productivity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1), 100-109.

(11) Criscuolo, C., Hijzen, A., Schwellnus, C., Barth, E., Chen, W.-H., Fabling, R., Fialho, P., Grabska, K., Kambayashi, R., Leidecker, T., Nordström Skans, O., Riom, C., Roth, D., Stadler, B., Upward, R., & Zwysen, W (2020). Workforce composition, productivity and pay: The role of firms in wage inequality. IZA DP No. 13212. Institute of Labor Eco- nomics (IZA).

(12) OECD. (2020). Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer. OECD Publishing

(13) OECD. (2020). Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer. OECD Publishing

(14) OECD. (2020). Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer. OECD Publishing

(15) . Cardoso, A. R., Guimarães, P., & Varejão, J. (2011). Are older workers worthy of their pay? An empirical investi- gation of age-productivity and age-wage nexuses. De Economist, 159(2), 95-111.

(16) Mitchell, E. M. (2019). Concentration of Health Expenditures and Selected Characteristics of High Spenders, US Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, 2016. Statistical Brief #521. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

(17) Costa‐Font, J., & Vilaplana‐Prieto, C. (2020). ‘More than one red herring’? Heterogeneous effects of ageing on health care utilisation. Health Economics, 29, 8-29.

(18) . Zweifel, P., Felder, S., & Meiers, M. (1999). Ageing of population and health care expenditure: A red herring? Health Economics, 8(6), 379–400.

Zweifel, P., Felder, S., & Werblow, A. (2004). Population ageing and health care expenditure: New evidence on the “red herring”. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance, 29(4), 652–666.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (2007). The value of life and the rise in health spending. The Quarterly Journal of Econo- mics, 122(1), 39–72.

Shang, B., Goldman, P. (2007). Prescription drug coverage and elderly Medicare spending. NBER Working Paper No. 13358.

(19) Felder, S., Werblow, A., & Zweifel, P. (2010). Do red herrings swim in circles? Controlling for the endogeneity of time-to-death. Journal of Health Economics, 29(2), 205–212

(20) . eshamani, M., & Gray, A. (2004). Ageing and health-care expenditure: The red herring argument revisited. Health Economics, 13(4), 303–314.

(21) Costa‐Font, J., & Vilaplana‐Prieto, C. (2020). ‘More than one red herring’? Heterogeneous effects of ageing on health care utilisation. Health Economics, 29, 8-29.

(22) . Gill, J., & Taylor, D. (2012). Active ageing: Live longer and prosper. School of Pharmacy, University College Lon- don.

(23) Axelrad, H., & Mahoney, K. J. (2017). Increasing the pensionable age: What changes are OECD countries ma- king? What considerations are driving policy?. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5(7), 56-70.

(24) Wainwright, D., Crawford, J., Loretto, W., Phillipson, C., Robinson, M., Shepherd S., Vickerstaff, S. & Weyman, A. (2019). Extending working life and the management of change. Is the workplace ready for the ageing worker? Ageing & Society, 39, 2397–2419.

(25) Salomon, R. H., & Solem, P. E. (2020). Nordic responses to extending working life. Nordic Welfare Research, 5(2), 75-82.

(26) Solem, P.E., Salomon, R.H. & Terjesen, H.C.A. (2020). Does a raised mandatory retirement age influence mana- gers’ attitudes to older workers? Nordic Welfare Research, 5(2), 122–136.

(27) Salomon, R. H., & Solem, P. E. (2020). Nordic responses to extending working life. Nordic Welfare Research, 5(2), 75-82.

(28) Midtsundstad, T. (2020). Traff vi blink? Refleksjoner rundt pensjonsreformen, økt yrkesdeltakelse og seniorpo- litikk. Nordic Welfare Research, 5(2), 140–145.

(29) Dang, T. T., Antolin, P., & Oxley, H. (2001). Fiscal implication of ageing: projections of age-related spending. Available at SSRN 607122.

(30) Zwijnenburg, J. & Goebel, P. (2017). Accounting for the financial consequences of demographic changes. In Chapter 9 in van de Ven, P. & Fano, D. (eds.), Understanding Financial Accounts (pp. 303-329). OECD Publishing

(31) Zwijnenburg, J. & Goebel, P. (2017). Accounting for the financial consequences of demographic changes. In Chapter 9 in van de Ven, P. & Fano, D. (eds.), Understanding Financial Accounts (pp. 303-329). OECD Publishing

(32) Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS). (2011). Gold age pensioners: Contribution outweighs cost by £40 billion. https://www.royalvoluntaryservice.org.uk/

(33) UK government Citizenship Surveys 2001-2011, www.communities.gov.uk/publications/Citizenshipsurvey

(34) Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS). (2011). Gold age pensioners: Contribution outweighs cost by £40 billion. https://www.royalvoluntaryservice.org.uk/

(35) Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS). (2011). Gold age pensioners: Contribution outweighs cost by £40 billion. https://www.royalvoluntaryservice.org.uk/

(36.) Griggs, M. J. (2010). Protect, support, provide: Examining the role of grandparents in families at risk of poverty. UK Equality and Human Rights Commission with Grandparents Plus.

(37) . Grundy, E. (2005). Reciprocity in relationships: Socio‐economic and health influences on intergenerational exchanges between third age parents and their adult children in Great Britain. The British Journal of Sociology, 56(2), 233–255.

(38) . Glaser, K., Montserrat, E. R., Waginger, U., Price, D., Stuchbury, R., & Tinker, A. (2010). Grandparenting in Europe. Grandparents Plus.

(39) SAPEA. (2019). Transforming the future of ageing. Evidence Review Report No. 5. Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA).

(40) PCAST. (2016). Report to the President: Independence, technology, and connection in older age. Executive Office of the President, President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST).

OSTP. (2019). Emerging technologies to support an ageing population. Task Force on Research and Development for Technology to Support Aging Adults, Committee on Technology, National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP).

(41) Bigonnesse, C., & Chaudhury, H. (2021). Ageing in place processes in the neighbourhood environment: a propo- sed conceptual framework from a capability approach. European Journal of Ageing, 1-12.

(42) Naylor, C. D. (2017). Investing in Canada’s future: Strengthening the foundations of Canadian research. Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science.

(43) Fritsch, L., Tjostheim, I., & Kitkowska, A. (2018, September). I’m Not That Old Yet! The Elderly and Us in HCI and Assistive Technology. In Proceedings of the Mobile Privacy and Security for an Ageing Population workshop at the 20th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services (MobileHCI), Barcelona, Spain.

(44) Roos, G. (2011). Establishing living labs to support public sector policy development. Briefing paper for the Regional Government in Gipuzkoa, ICS, London.

(45) Laperche, B., Boutillier, S., Djellal, F., Ingham, M., Liu, Z., Picard, F., Reboud, S., Tanguy, C., & Uzunidis, D. (2019). Innovating for elderly people: The development of geront’innovations in the French silver economy. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 31(4), 462–476.(46) Lepik, K. L., & Krigul, M. (2021). Expectations and needs of Estonian health sector SMEs from living labs in an international context. Sustainability, 13(5), 2887.

(47) Schuurman, D. (2015). Bridging the gap between open and user innovation? Exploring the value of living labs as a means to structure user contribution and manage distributed innovation (Doctoral Dissertation, Ghent Uni- versity).

(48). Leminen, S. (2013). Coordination and participation in living lab networks. Technology Innovation Management Review, 3(11), 5–14.

(49) Gourville, J. T. (2005). The curse of innovation: A theory of why innovative new products fail in the marketplace. HBS Marketing Research Paper, (05–06).

(50) Alasoini, T. (2011). Workplace development as part of broad-based innovation policy: Exploiting and exploring three types of knowledge. Nordic journal of working life studies, 1(1), 23–43.

(51) Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84–92.

(52) Roos, G., & Agarwal, R. (2015). Services innovation in a circular economy. In R. Agarwal, W. Selen, G. Roos, & R. Green (Eds.), The handbook of service innovation (pp. 501–520). Springer.

(53) Dell’Era, C., & Landoni, P. (2014). Living Lab: A methodology between user‐centred design and participatory design. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(2), 137–154.

(54) Schuurman, D., De Marez, L., & Ballon, P. (2013). Open innovation processes in living lab innovation systems: Insights from the LeYLab. Technology Innovation Management Review, 3(11), 28–36.

(55) Malmberg, K., & Vaittinen, I. (2017). Living lab methodology handbook. U4IoT Consortium. https://u4iot. eu/ pdf/U4IoT_LivingLabMethodology_Handbook. pdf

(56) http://www.aal-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/20210127_BirgitMorlion_AAL_Call2021_infoday.pdf

(57) van Staalduinen, W., Spiru, L., Illario, M., Dantas, C., & Paul, C. (2021). D4 Report on SHAFE policies, strate- gies and funding. International Interdisciplinary Network on Smart Healthy Age Friendly Environments | NET4A- ge-Friendly. COST Action 19136 (20202024).

(58) https://www.aging2.com/grandchallenges/

(59) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy-the-grand-challenges/missions

(60) . Technopolis. (2015). A Mapping of Smart Ageing Activity in Ireland and An Assessment of the Potential Smart Ageing Opportunity Areas. An independent report for the Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation. tech- nopolis |group|.

DJEI (2015). Innovative Agile Connected. Enterprise 2025. Ireland’s National Enterprise Policy 2015-2025. Back- ground Report. Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation (DJEI)

(61) Menet, N. (2019). Silver Valley, an Innovation Ecosystem Supporting Longevity. AARP International: The Journal, 12, 58-59.

(62) Oget, Q. (2021). When economic promises shape innovation and networks: A structural analysis of technologi- cal innovation in the silver economy. Journal of Innovation Economics Management, (2), 55-80.

(63) Sourced from https://i0.wp.com/www.thegerontechnologist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021-Age- Tech-Market-Map-3.png?resize=1448%2C2048&ssl=1

(64) Iparraguirre J.L. (2019) The Silver Economy. Chapter 12 in: Iparraguirre J.L. (2019) Economics and Ageing. Palgrave Macmilla

(65) SAPEA. (2019). Transforming the future of ageing. Evidence Review Report No. 5. Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA).

(66) Ayalon, L., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2018). Contemporary perspectives on ageism. Springer Nature.

(67) Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Ebrahim, S., McKee, M., & Prince, M. (2015). A premature mortality target for the SDG for health is ageist. The Lancet, 385(9983), 2147-2148.

(68) Dennis, H., & Thomas, K. (2007). Ageism in the workplace. Generations, 31(1), 84-89.

(69) Gewirtz‐Meydan, A., & Ayalon, L. (2017). Physicians’ response to sexual dysfunction presented by a younger vs. an older adult. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(12), 1476-1483.

(70) Ouchida, K. M., & Lachs, M. S. (2015). Not for doctors only: Ageism in healthcare. Generations, 39(3), 46-57.

(71) Higgins, I., Der Riet, P. V., Slater, L., & Peek, C. (2007). The negative attitudes of nurses towards older patients in the acute hospital setting: A qualitative descriptive study. Contemporary Nurse, 26(2), 225-237.

Higashi, R. T., Tillack, A. A., Steinman, M., Harper, M., & Johnston, C. B. (2012). Elder care as “frustrating” and “bo- ring”: understanding the persistence of negative attitudes toward older patients among physicians-in-training. Journal of Aging Studies, 26(4), 476-483.

Liu, Y. E., Norman, I. J., & While, A. E. (2013). Nurses’ attitudes towards older people: A systematic review. Interna- tional journal of nursing studies, 50(9), 1271-1282.

(72) Shippee, T. P. (2009). “But I am not moving”: Residents’ perspectives on transitions within a continuing care retirement community. The Gerontologist, 49(3), 418-427.

(73) Vitman, A., Iecovich, E., & Alfasi, N. (2014). Ageism and social integration of older adults in their neighborhoods in Israel. The Gerontologist, 54(2), 177-189.

Ayalon, L. (2015). Perceptions of old age and aging in the continuing care retirement community. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(4), 611-620.

Noon, R. B., & Ayalon, L. (2018). Older adults in public open spaces: Age and gender segregation. The Gerontolo- gist, 58(1), 149-158.

(74) Aliramaei, S. (2021). Skanshuset: health promotive intergenerational co-housing project (Master Thesis, Chal- mers School of Architecture, Department of Architecture & Civil Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology)

(75) Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Kunkel, S. R., & Kasl, S. V. (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(2), 261-270.

(76) Levy, B. R. (2003). Mind matters: Cognitive and physical effects of aging self-stereotypes. The Journals of Ge- rontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(4), P203-P211.

(77) Ayalon, L. (2016). Satisfaction with aging results in reduced risk for falling. International psychogeriatrics, 28(5), 741-747.

(78) Levy, B. (1996). Improving memory in old age through implicit self-stereotyping. Journal of personality and social psychology, 71(6), 1092-1107.

(79) Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Murphy, T. E., & Gill, T. M. (2012). Association between positive age stereotypes and recovery from disability in older persons. Jama, 308(19), 1972-1973.

(80. Ayalon, L. (2018). Loneliness and anxiety about aging in adult day care centers and continuing care retirement communities. Innovation in Aging, 2(2), igy021.

(81) Cebulla, A., & Wilkinson, D. (2019). Responses to an ageing workforce: Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom. Business Systems Research: International journal of the Society for Advancing Innovation and Research in Eco- nomy, 10(1), 120-137.

(82) Ní Léime, Á., Ogg, J., Rašticová, M., Street, D., Krekula, C., Bédiová, M., & Madero-Cabib, I. (Eds.). (2020). Exten- ded Working Life Policies. International Gender and Health Perspectives. SpringerOpen.